For more than a decade, Nigerian security services and their international supporters have struggled to end Boko Haram’s brutal reign of terror over northeastern Nigeria.

But few observers of the conflict are celebrating – even though it appears increasingly likely that Abubakar Shekau, the Islamist extremist movement’s notoriously violent leader, is dead, its strongholds overrun and remaining fighters scattered.

The reason is simple: the force that defeated Shekau’s Boko Haram was not fighting under the green and white national flag of Nigeria, but the black flags of the Islamic State.

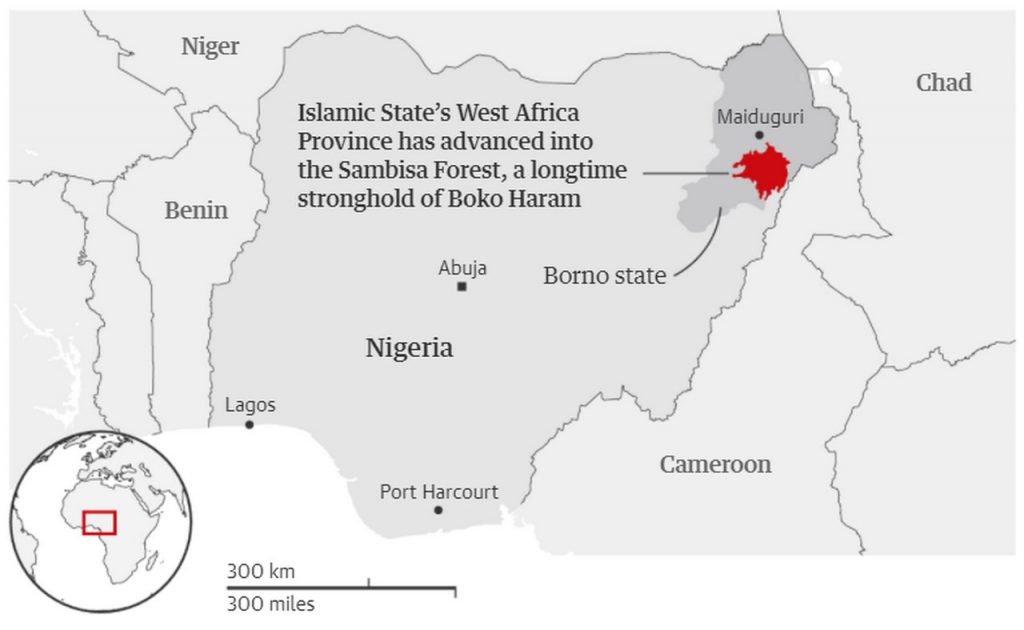

The battle on Wednesday was the culmination of a campaign by Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) to eliminate a group its own leaders saw as a rival and potential threat. Moving from bases to the east, around Lake Chad, ISWAP mobile columns swept into the thick brush of the vast Sambisa Forest and cornered Shekau. This was something Nigerian forces, despite the dispatch of multinational taskforces put together by western governments and vast sums of aid, had been unable to do in 12 years of fighting.

Some sources reported Boko Haram fighters joining the victors. Assuming he is dead, ISWAP will also acquire Shekau’s stocks of weapons, ammunition, and treasury.

On the strategic level, the takeover of Boko Haram’s territory in the northeast of the country will anchor a zone stretching thousands of miles across the region all the way through hotspots such as Mali to the Libyan border where Isis-affiliated groups hold sway.

The Isis-linked groups were not always as dominant in the region. For many years al-Qaida was the leading extremist organization in much of the Sahel, even after the rise of its rival in 2014. But when the two groups started to clash 18 months ago after a long period of cohabitation, it was Isis that came off best. This superiority has allowed it to benefit most from the expansion of Islamism across the region.

The HumAngle website, run by well-informed Nigerian reporters with sources inside local intelligence services and extremist networks, has reported that the Iswap attack on Boko Haram was greatly aided by senior commanders within Shekau’s group who had switched sides. These included some who stayed within Boko Haram, feeding intelligence to Iswap commanders.

Many may have been influenced by the relative weakness of Boko Haram, which has suffered from military airstrikes on its bases in the Sambisa Forest and heavy losses inflicted by troops in neighboring Chad.

Their defection is also a gauge of extremist sentiment elsewhere and is likely to signal a surge of support for Isis affiliates in places such as Niger, Burkina Faso, and the key battleground of Mali.

In Nigeria, the death – or possible incapacity – of Shekau would mark the end of an era.

Shekau took over Boko Haram – formally known as Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad – after its founder, Mohammed Yusuf was killed by police in 2009 and took its violence to new levels.

Under his leadership, the group pioneered the use of children and women as suicide bombers and turned large swathes of the northeast into a no-go zone for government officials and forces, proclaiming a short-lived “caliphate” in the town of Gwoza in Borno state in 2014.

An offensive since 2015 by Nigerian troops backed by soldiers from Cameroon, Chad, and Niger drove jihadists from most of the area that they had once controlled.

Shekau’s tactics led dissidents within Boko Haram to break away in 2016 to form Iswap with the backing of Isis leaders in Iraq and Syria. The new group quickly evolved into the more capable and disciplined force, with a much more sophisticated “hearts and minds” policy towards local communities than Shekau ever implemented.

This too may be one reason for the shifting balance of power among the extremists, and will also be seen as a lesson for other militant Islamist groups around the continent.

Though often tenuous, links established by “Isis central” to insurgencies in Mozambique and parts of the central Great Lakes region have allowed the group to give the impression that gains in Africa have compensated for some of its losses in its Middle East heartland. With the effective takeover of an enduring insurgent campaign in the continent’s most populous state, the propaganda now has some genuine substance.

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV