There’s a fine line between being hailed as a visionary and being denounced as a crank, as Iraq-born physicist Jim Al-Khalili is only too aware. Seated in his office at the University of Surrey in the U.K. on a sunny day, he recalls a less tranquil time in his career, almost 15 years ago. Back then, he and his Surrey colleague, biologist Johnjoe McFadden, explored a strange mechanism to explain how DNA — the molecule that carries our genetic code — may mutate.

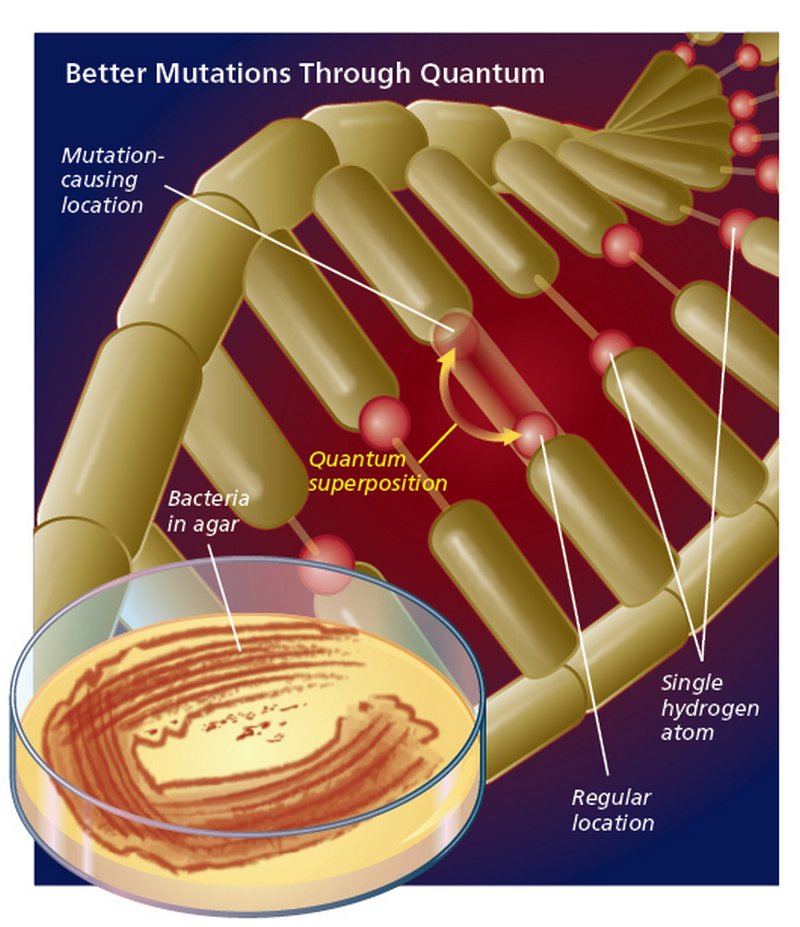

Their theory caused a stir because it invoked quantum mechanics, the branch of physics that describes the behavior of particles in the subatomic realm. Their idea gave some insight into the origins of genetic mutations, which over the centuries have given rise to the variety of species in the biological kingdom, and in the short term can lead to the development of diseases like cancer. The proposal was scoffed at, however, sparking incredulity from both biologists and physicists because quantum effects supposedly hold sway only on the smallest scales and cannot govern large biological molecules.

“Senior colleagues in physics warned me of this line of research, saying, ‘This isn’t just speculative, it’s wacky,’ ” Al-Khalili says. “I have since realized that some of the best ideas come out of seemingly crazy thoughts because otherwise, they wouldn’t be new.”

Though Al-Khalili and McFadden did not label it as such at the time, their paper was one of the first in the now burgeoning field of quantum biology. The strange rules that control the subatomic world might be unintuitive, but they have been verified through many experiments for the better part of a century. Yet it is only in the past decade or so that a small but dedicated band of physicists and biologists has found hints that nature may also use these rules to enhance the efficiency of biological tasks.

If true, then physicists struggling to innovate in the lab could take a quantum leaf out of nature’s book and learn how to devise better machines. Even more ambitiously — and controversially — some argue that quantum biology could be a game-changer in treating serious diseases. “The holy grail is to find that quantum effects stimulate biological processes that are relevant to medicine,” says Al-Khalili. “Looking to the long term, if these effects underlie the mechanism of DNA mutations, that could allow for real progress in the treatment of cancer.”

Quantum in the Quotidian

The seeds for Al-Khalili’s interest in biology were sown in 1960s Baghdad when his parents gave him a microscope for Christmas. At the time, biology was all the rage: In 1953, Cambridge University biophysicists Francis Crick and James Watson had discovered that DNA takes the form of a double helix or a twisted ladder. Al-Khalili’s parents hoped that their son would develop an interest in this exciting new science, but to their despair, he was far too preoccupied with football and music.

A few years later, however, at the age of 13, he fell in love — not with biology, but with physics, when he realized that mathematics could predict the outcome of high school experiments. “I suddenly understood that common sense was the route to answering deep questions about the way things worked,” he says. Ironically, this love of logic was severely tested when he later embarked on an undergraduate degree in physics at the University of Surrey and learned that, at the fundamental level where quantum laws take over, everyday rules fly out the window.

Now in his 50s, Al-Khalili’s face lights up and he becomes as animated as a teenager, waving his hands in frustration when he recalls his first encounters with quantum mechanics. For instance, the phenomenon of superposition states that before you look, a particle has no definite location. Only when the position of the particle is measured does it randomly settle into one spot. “We were told things like this very dryly,” says Al-Khalili. “The lecturers didn’t like me asking what it actually means to say that something can be in two places at the same time.”

Another perplexing oddity is known as quantum tunneling: In the microscopic realm, particles can travel across barriers that, in theory, they should not have the energy to get through. Al-Khalili remembers his lecturer trying to illuminate the topic by explaining, “It’s as if I were able to take a run up at this wall, and instead of crashing into it, I would suddenly appear, intact, on the other side.” He says the weirdness of the quantum world still frustrates him.

As strange as they are, these quantum characteristics have been demonstrated time and again in the lab, as Al-Khalili discovered when he later specialized in nuclear physics, the study of particles within the atom. By the mid-’80s, as he was establishing his early career, physicists had become so comfortable with the bizarre behavior of quantum objects that they began to ponder exploiting them to build powerful machines.

Whereas modern computers process information encoded in binary digits (or bits) that take the value of either 0 or 1, physicists realized that so-called quantum computers could store information in “qubits” that can exist in superposition, simultaneously both 0 and 1. If multiple qubits could be strung together, they reasoned, it should be possible to construct a quantum processor that performs calculations at speeds that are unimaginably quicker than standard devices. For instance, while current computers search through databases by examining each entry separately, a quantum computer would be able to look at all entries simultaneously.

The idea that plants and animals may already be carrying out such superfast quantum operations within their own cells, however, did not seriously cross the minds of either physicists or biologists, even though cells are made up of atoms and, at a basic level, all atoms obey quantum mechanics. The main reason was that, as the would-be builders of quantum computers discovered, quantum effects are extremely fragile. To maintain superposition in the lab, physicists need to cool their systems down to almost absolute zero, the lowest temperature possible, because heat can destroy quantum features. So there seemed little chance that these quantum properties could survive in the balmy temperatures within living cells.

But in the late 1990s, Al-Khalili realized that this assumption may have been too hasty when he first met McFadden, who introduced him to a biological mystery whose solution might require quantum help.

Mutations 101

At the time, McFadden, a member of Surrey’s biology department, wanted to ask physicists for advice about how to handle a puzzle regarding DNA mutations. He and his colleagues had been investigating the genetic makeup of a nonlethal cousin of M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, and they found that under special circumstances — when held in conditions nearly devoid of oxygen — the bacteria mutated in a way that made it especially virulent. What surprised the team was that this particular mutation seemed to occur at a more frequent rate than other mutations.

McFadden, like all good biologists, had learned that no such enhancement should occur. The central dogma since the 19th century, when Charles Darwin formulated the idea that mutations create the genetic variation needed for species to evolve, has been that all mutations should happen at random. No single type of mutation should occur more often than another, no matter what the environment. Certain mutations may prove useful, but the environmental conditions themselves should not play a role in the rate of any particular genetic mutation: Evolution is blind. McFadden’s team, however, seemed to have found a case that defied standard evolutionary theory, since the lack of oxygen in the experiment’s environment appeared to be triggering one type of mutation over others.

This was not the first time he had heard about such controversial findings. A decade earlier, in 1988, a group of molecular biologists led by John Cairns at the Harvard School of Public Health published startling results showing similar adaptive mutations. When they spread a strain of E. coli that could not digest lactose onto an agar plate whose only food source was lactose, they found that the bacteria developed the mutation required to digest the sugar at a far faster rate than expected if that mutation occurred at random. It looked like this adaptation had somehow resulted from the environment. “The study was absolutely heretical in the Darwinian sense,” says McFadden. Nonetheless, the experiments were respected enough to be published in the prestigious journal Nature.

In search of a possible mechanism that could explain just how the environment might do this, McFadden’s mind turned to popular accounts he had read about quantum computing that explained how superposition could significantly speed up otherwise slow processes. With that vague thought, McFadden asked his university’s physics department if quantum processes might explain the TB adaptations. His audience did not welcome the idea. “Most of my physicist colleagues thought he was naïve, and the idea that quantum effects might play a role in adaptive mutations was ridiculous,” recalls Al-Khalili.

Yet Al-Khalili — no stranger to potentially embarrassing questions — was intrigued enough to discuss the problem. “Don’t imagine that we sat there with some grand vision that we were pioneering quantum biology,” laughs Al-Khalili. “Really we just enjoyed meeting up once a week at Starbucks to chat through things we both found fascinating.” It paid off. Over the course of a year, they hashed out a theory using quantum mechanisms to explain how adaptive mutations occur.

The Quantum Solution

DNA’s twisted ladder structure requires rungs of hydrogen bonds to hold it together; each bond is essentially made up of a single hydrogen atom that unites two molecules. This means sometimes a single atom can determine whether a gene mutates. And single atoms are vulnerable to quantum weirdness. Usually, the single atom sits closer to a molecule on one side of the DNA ladder than the other. Al-Khalili and McFadden dug out a long-forgotten proposal made back in 1963 that suggested DNA mutates when this hydrogen atom tunnels, quantum-mechanically, to the “wrong” half of its rung. The pair built on this by arguing that, thanks to the property of superposition, before it is observed, the atom will simultaneously exist in both a mutated and non-mutated state — that is, it would sit on both sides of the rung at the same time.

In the case of the fast-adapting E. coli, that would correspond to its DNA being primed to both enable the bacteria to eat lactose and also not be able to eat lactose. Al-Khalili and McFadden mathematically analyzed the interactions between the single hydrogen atom in the germ’s DNA and its surrounding lactose molecules. The presence of the sugar molecules jostling the atom has the effect of “observing” it, they argue, forcing the hydrogen to snap into one position, just as measuring the state of any quantum particle will fix it to one set location. What’s more, their calculations showed that the mutation that would enable E. coli to digest lactose would occur at a faster rate than in the absence of sugar. “It was hand-waving, but we had an inkling that something quantum was happening at the level of DNA,” says Al-Khalili. He and McFadden had joined a small group of mavericks who dared to link biology and quantum physics.

Not everyone was convinced. Many of Al-Khalili’s colleagues advised him to drop this fool’s errand, arguing that no experiments had definitively shown that quantum effects play a role in biological molecules. Given the state of biological imaging at the time, verifying the pair’s theory directly seemed impossible. In the meantime, Cairns’ original E. coli study had also come under close scrutiny. The increased rate of lactose-digesting mutations was independently reproduced a number of times, says McFadden, but there were suggestions that other non-beneficial mutations might also be enhanced, too — possibly obviating the need to invoke quantum mechanics. “It was around then that we lost interest in the subject,” says McFadden. Both he and Al-Khalili forgot their lofty ambitions and returned to their day jobs.

Work Continues

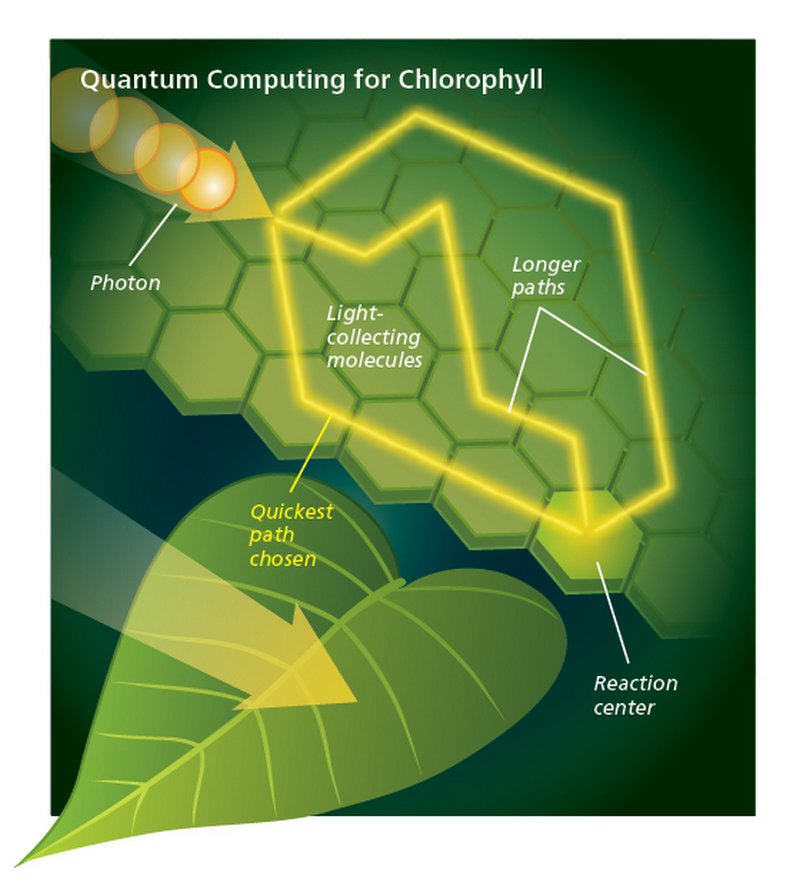

Looking back, Al-Khalili admits they were too easily swayed. In the following years, a host of experimental results sprang up hinting that quantum effects may be at work in many different corners of the biological world. The most significant appeared in 2007 and involved photosynthesis, the process by which chlorophyll molecules in plants convert water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight into energy, oxygen, and carbohydrates.

Photosynthesis achieves a whopping 95 percent energy transfer efficiency rate, “more efficient than any other energy transfer process known to man,” says McFadden. Within chlorophyll, so-called antenna pigments guide energy from light-collecting molecules to nearby reaction-center proteins along a choice of possible pathways. Biologists had assumed that the energy hopped from molecule to molecule along a single pathway. But calculations showed that this could account only for about a 50 percent efficiency rate. To explain the near-perfect performance of plants, biophysicists reasoned, the energy must exist in a quantum superposition state, traveling along all molecular pathways at the same time — similar to the quantum computer that could simultaneously search all entries in a database. Once the quickest road is identified, the idea goes, the system snaps out of superposition and onto this route, allowing all the energy to take the best path every time.

In the 2007 experiment, University of California, Berkeley, chemist Graham Fleming, and colleagues ran experiments on green sulfur bacteria that appeared to suggest this quantum approach. Fleming’s work took place at minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit, but similar effects appeared three years later in experiments with marine algae carried out at room temperature by a team led by Gregory Scholes, a chemist at the University of Toronto in Ontario. “These were jaw-dropping experiments,” says McFadden. “Physicists had been battling for years to build a quantum computer — and now it seemed that all that time they may have been eating quantum computers for lunch, in the leaves in their salad!”

Vlatko Vedral — a physicist who whimsically describes himself as being quantum superimposed at both the University of Oxford in the U.K. and the Centre for Quantum Technologies in Singapore — took notice. “Up to then, all these ideas in quantum biology sounded good, but they lacked experimental evidence,” he recalls. “The photosynthesis experiments changed people’s minds.” Although he adds, critics have pointed out that the tests use artificial light from lasers, rather than natural sunlight. It remains unclear whether the same quantum effects observed in tightly controlled lab conditions really do occur outdoors in our gardens.

The experiments were enough to set Vedral wondering if he and his colleagues could find quantum effects within the animal equivalent of photosynthesis. The energy factory in animal cells like our own is the mitochondrion, a repository for channeling energy from glucose harvested from food into electrons. These high-energy electrons are then shuffled through a cascade of reactions to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecule that fuels most cellular work. Conventional biological models described the electrons as hopping from molecule to molecule within mitochondria, but — once again — this simple picture cannot account for the speed at which ATP is spitting out.

Vedral’s team has come up with a model in which, rather than hopping, the electrons exist in a quantum superposition, smeared out at once across all the molecules in the ATP production line. Their calculations predicted a boosted ATP production rate, as seen in experiments. Once again, it was a quantum solution to a biological mystery.

Uncertain Future

Though still tentative, the possible health ramifications of these theories have not gone unnoticed. Vedral notes that failure in electron transfer in mitochondria has been linked to Parkinson’s disease and to some cancers. The connection is still speculative, he admits, because the precise cause-and-effect relationship between the two is murky. “Does the failure of electron transfer lead to the disease, or does the disease cause the breakdown of electron transfer?” Vedral asks. “That’s something biologists don’t know, and we have to look to them for an answer.”

Nonetheless, because the payoff could be so high, the conjecture has attracted the first major research grant enabling the Oxford group, led by Oxford physicist Tristan Farrow, to run their own experiments into quantum biology. The grant stands as one of the biggest stamps of approval for this controversial discipline, which until now has largely been a topic for researchers’ spare time. As Farrow walks me around the darkened lab where these tests will take place, he explains that it’s arduous work, and it can take up to five years to prepare.

The first task, says Farrow, will be to verify the 2007 photosynthesis results; after this, the team will study the larger and more complex molecules involved in mitochondrial energy transfer. Farrow explains that he personally is driven not so much by the potential medical benefits that helped lead to the grant — which will come many years down the road, if at all — but by the hope that nature could teach us how to build better machines.

“If we can show that quantum effects survive for a long time in biological molecules and work out how that happens, then we can use that information to design better quantum computers in the lab,” he says. McFadden agrees: “If we could understand how photosynthesis is so efficient at transforming sunlight into energy and re-create that artificially, then today’s poorly performing solar cells would be a thing of the past.”

Physicists struggling to string together more than a handful of qubits at ultracold temperatures in the lab are also keen to discover just how biomolecules can apparently shield fragile quantum effects so that they can be exploited by living systems without disruption. “A benefit of studying quantum effects in biological systems is to learn if and how nature protects them, so that we may copy the architecture of the natural building blocks,” says Farrow. Quantum computers must operate at room temperature if they are ever to be used in mainstream applications. “Such blocks could then be used as the basic units in ‘biological’ quantum computers,” Farrow adds.

A decade ago, such experiments would have been impossible because the technology to manipulate single biological molecules did not exist. These improvements in experimental techniques, combined with the advances made by others in quantum biology, have inspired McFadden and Al-Khalili to leave the sidelines and rejoin the game. “We started to think, ‘Hang on, maybe we were onto something all those years ago,’ ” Al-Khalili laughs. As a mark of just how much the tide has turned, in January 2013, Al-Khalili gave a talk about his ideas on quantum tunneling and DNA mutations at the Royal Institution, London’s prestigious scientific establishment.

Al-Khalili and McFadden are also about to embark on the first set of tests of their mutation theory. Their proposed experiments compare the behavior of normal DNA molecules with specially modified DNA molecules whose hydrogen atoms have been replaced with deuterium atoms (also known as heavy hydrogen because the atoms have the same chemical properties as hydrogen, but double the mass). If they’re right that mutations are caused when a hydrogen atom tunnels quantum-mechanically to the wrong side of DNA’s ladder, then they predict that the rate of mutations will be significantly lower in the modified DNA molecules since heavier deuterium is less likely to tunnel across the ladder.

But all of these tests will take a few years to design and carry out. Surveying the lasers and mirrors laid out on Farrow’s laboratory table in Oxford, he notes that the road to definitive experimental proof of quantum biology will be a long one — and there is a very real chance they will never prove quantum effects lurk within living beings.

“There is a huge risk that we may be heading in the wrong direction,” Farrow says ruefully. “But my hunch tells me this is worth it because if we succeed, the payoff will be massive: We will have pioneered a new discipline.”

[This article originally appeared in print as “This Quantum Life.”]By Zeeya Merali

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV