The Nauru president who allowed Australia to reopen a controversial detention camp for asylum seekers on the tiny Pacific island has said that he made a “deal with the devil.”

In 2012, Sprent Dabwido gave then-Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard the go-ahead for the facility, which Amnesty International later slammed as an “open-air prison.”

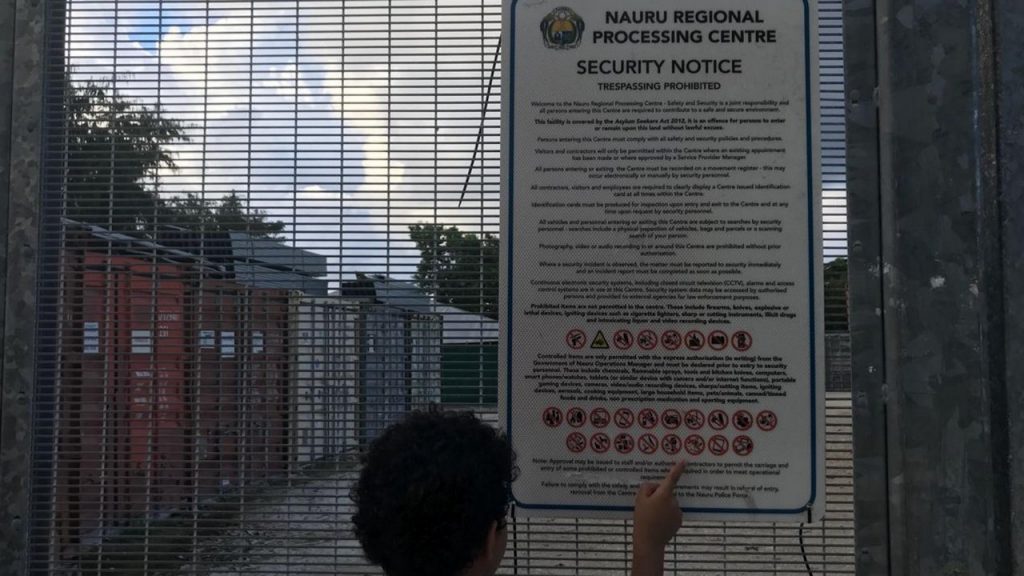

For years, the Australian government has sent asylum seekers who arrive in its waters by boat to offshore processing centers on Nauru and on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island.

The detainees were told they would never be settled in Australia if they came by boat. Canberra says tough border protection policies are necessary to avoid deaths at sea at the hands of people smugglers.

But the offshore processing centers were highly controversial. Human rights groups criticized the poor living conditions and a high incidence of mental health problems among detainees.

Keeping asylum seekers on the island, which is home to under 10,000 people, for years without hope of getting to Australia had amounted to “torture,” Dabwido told The Project on Australia’s Network 10 on Wednesday.

“Nauru government should find a better way than living on these people’s blood,” he added.

Dabwido, who presided over Nauru from 2011 to 2013, made the frank comments in what he said would “most likely” be his last interview before succumbing to a battle with terminal cancer.

The former president is himself now seeking asylum in Australia, after clashing with the Nauru government over a political rally at the country’s parliament in 2015.

As Dabwido reflected on his time in office, he said his decision had “turned our country upside down.” “I thought I was doing the right thing,” he said.

Australia has spent almost $5 billion Australian ($3.6 billion) on offshore processing facilities on Nauru and Manus Island since 2012, broadcaster ABC reported last year.

That investment has boosted Nauru’s economy. In the 2013-14 financial year, income from visa fees alone tripled to around $18 million Australian ($13 million) compared with the previous year, ABC reported.

When asked by The Project reporter whether he felt he had “done a deal with the devil,” Dabwido replied that he didn’t believe so at the time. “Now, though, I think the deal on the table was done by the devil,” he said. “It is a deal with the devil.”‘

By the end of March 2019, all remaining refugees and asylum seekers had moved out of the Nauru Processing Center, according to the Australian government. The Refugee Council of Australia says around 350 refugees are living among the Nauru community.

An Australian government spokeswoman said regional processing arrangements had kept Australia’s borders secure.

“Refugees and non-refugees in Nauru live in the community, they are not detained,” the spokeswoman said in a statement. Health and welfare services are provided.

Every child asylum-seeker has been removed from Nauru, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said in February.

But Katie Robertson, the legal director of Australia’s Human Rights Law Center, said Dabwido’s comments were a “damning indictment” of the policy.

“For six long years, refugees in Australia’s care on Nauru have been subjected to an unconscionably cruel and brutal regime of indefinite detention,” she said. “Over this time, we’ve seen a humanitarian crisis unfolding.”

At its peak in August 2014, the Nauru detention center housed over 1,200 asylum seekers, including 222 children and 114 women, according to Australian government data.

In October 2015, Nauru announced that asylum-seekers would no longer be detained at the center and would instead be free to move around the island.

Last year, a United Nations official described the mental health conditions of detainees on Nauru as “shocking,” noting serious issues including self-harm among children.

There were claims of rape at the detention center, including a 10-year-old boy in 2014. In 2016, a refugee died after setting himself on fire, and as recently as last year a 12-year-old boy was airlifted to Australia for medical treatment after refusing to eat for at least two weeks.

Many of the refugees have now been resettled in the United States thanks to a deal between former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and former US President Barack Obama.

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV