The military build-up continues ‘like never before’ on both sides of the 2,100-mile border despite high-level talks

It was described as a dialogue, the first high-level meeting in months between the Indian and Chinese foreign ministers to address the ongoing border aggressions that have pushed the two nuclear-armed countries to the brink of war.

But those hoping Wednesday’s meeting would help break a year-long stalemate during which 200,000 troops have built up on both sides of the Himalayan frontier were to be left unsatisfied.

There was one point of agreement, however. As Wang Yi, the Chinese foreign minister, noted, “relations between India and China are still at a low point”.

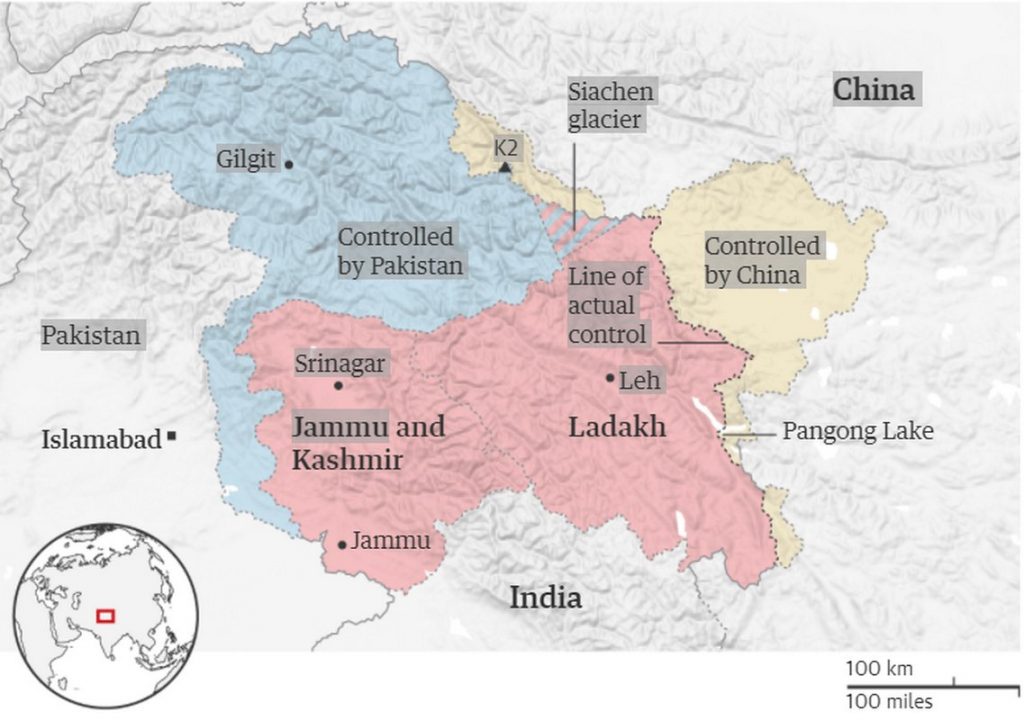

In June last year, following several months of rising tensions along the India-China border in the Himalayan region of Ladakh, 20 Indian soldiers and reportedly four Chinese soldiers were killed in the deadliest clash between the two countries in more than 50 years. Forbidden from firing weapons, the two sides instead fought on the icy mountain precipice of Galwan valley in medieval fashion, using spiked clubs and engaging in hand-to-hand combat, with several soldiers falling to their deaths.

The clash did not result in all-out declarations of war, but pledges of de-escalation and multiple rounds of failed military talks have instead been overshadowed by a year of troop, artillery and infrastructure buildup on both sides of the 2,100-mile border unlike at any other time in history, including when China invaded India in 1962.

Indian army officials allege the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is becoming more aggressive with every passing day. Though recent skirmishes between the two sides have been denied by the Indian government, army officials told the Guardian that the situation in areas of eastern Ladakh including Galwan valley and Hot Springs remained extremely tense.

“Every month there are two to three face-offs in these areas,” said another army officer posted in the area, the information corroborated by local police and intelligence officers.

“To avoid further escalations we started fencing some areas around Galwan but Chinese objected to it and we had to remove it,” said another officer.

The ministry of defence and the military did not respond to requests for comment.

Indian army officers described the military buildup on the border in Ladakh as “like never before”. Government sources corroborated reports that an additional 50,000 troops, as well as artillery and fighter planes, including the Russian-made MiG-21, had been deployed.

In a sign of the shift in Indian military priorities, some of the additional troops on the Chinese border, including Ladakh and the states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, have come from the border with Pakistan, which for decades was India’s most turbulent frontier.

The greatest test for both sides was surviving the hostile winter, where temperatures dropped to below 40 degrees. Yet Indian officers spoke of proudly staying the course, even when it got so cold that the fuel in the tanks froze. Despite the glacial temperatures, the soldiers have to stay in tents that can be moved quickly.

“We should have prefabricated living spaces given the harsh weather,” said an Indian army commander posted in the region. “But due to the unpredictability of Chinese moves, we are relying on tents as they can be relocated quickly whenever needed.”

While Indian army officers say they cannot match the hightech Chinese infrastructure, they at times admitted to copying their way of living. “For instance, we saw Chinese would dig trenches and then put tents in them,” said an army officer. “We realised it helps warm up the canopy and since then we have been doing that way.”

For locals in the Indian state of Ladakh, who have spent a year witnessing soldiers, tanks, helicopters and heavy artillery brought up along the frontier, fear remains palpable.

“I hope war never breaks out here,” said Dolma Dorjay, who grew up in the village of Chushul near a sprawling army base along the line of actual control [LAC], the unmarked disputed border between India and China. “But the preparations seem to be happening for a war.”

Prior to the clash at Galwan, Dorjay and most of the villagers, who are tribal Changpa cattle herders, would take their livestock into the vast, sweeping valleys without another thought of the border and would freely mingle with the shepherds from the Chinese side. “We would trade cattle and carpets and more with the people of the other side,” he said.

Sonam Tsering, another resident and former local councillor of Chushul, said the situation along the border was the most militarised anyone in the village could recall, with two armies appearing to be poised for attack, particularly in areas of eastern Ladakh.

“Our elders say that men and machinery were not deployed like this even in the 1962 war,” he said. “The army base in Chushul has expanded multiple times. Now people are not allowed to go near the border and tourists are banned from visiting.”

Durbuk is another strategic military base in eastern Ladakh that has vastly expanded. The locals say that hundreds of new tents have been pitched in recent months to accommodate more and more arriving soldiers, while new structures have been put up to shield tanks and bigger vehicles.

Deldan, who operates a guest house in Durbuk village, described how “during the night, we see large convoys of army trucks and tanks heading towards the border”.

In some of the tensest areas, a buffer zone has been agreed upon between Indian and Chinese troops to prevent troops coming to blows, and according to the Chinese foreign minister frontline troops have “disengaged in the Galwan Valley and the Pangong Lake area”. But locals say this does not reflect the reality on the ground and are dismissive of any talk of de-escalation.

In the Pangong lake, locals say India has not regained territory where the Chinese encroached. “The land which belonged to us is now the buffer zone,” said Padma Yangdog, a resident of Meerak, a village opposite an area of Chinese encroachment. “How have they [Chinese troops] moved back?”

As made clear when Jaishankar and Wang met at the sidelines of a gathering of foreign ministers in Tajikistan on Wednesday, India and China still have starkly different views on the border situation.

Jaishankar said it was only with China’s de-escalation and disengagement from the border that formerly cordial bilateral ties could be resumed. Wang, however, said that “the responsibility does not lie with China” to resolve the issue, and appeared to call on India to accept the current status quo in the interest of good relations. According to Wang, despite the heavy troop presence, “the situation in the China-India border area has generally been easing”.

Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in Delhi, said it was clear India and China “are now locked in an uneasy military stalemate, and the entire frontier has become a hot border”.

“The Chinese tried to ward off India through a frenzied military buildup but the Indians have refused to buckle,” he said. “The fact that the Indians managed to stay put through the harsh Himalayan winter makes it quite likely that this crisis is not going to end anytime soon.”

According to Chellaney, “the only way to break the stalemate is if the Chinese decide to start a war. But, as the Chinese realise, even all-out conflict is likely to still end in another stalemate.”

“With India refusing to back down, the choice for China is to either quietly roll back its intrusions in areas where the biggest standoffs are taking place,” he said, “or to let this deadlock continue.”

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV