Around 12 million hectares of forest in the world’s tropical regions were lost in 2018, equivalent to 30 football fields per minute.

While this represents a decline in 2016 and 2017, it is still the fourth highest rate of loss since records began in 2001.

Of particular concern is the continued destruction of what are termed primary forests.

An area of these older, untouched trees the size of Belgium was lost in 2018.

The Global Forest Watch report paints a complex picture of what’s going on in the heavily forested tropical regions of the world that range from the Amazon in South America, through West and Central Africa to Indonesia.

The forests of the Amazon basin are home to an estimated 20 million people. Among them are dozens of tribes living in voluntary isolation.

As well as providing food and shelter, the trees in these regions are important to the world as stores of carbon dioxide and play a key role in regulating global climate change.

Millions of hectares of these forests have been lost in recent decades, having been cleared by commercial or agricultural interests.

The data from 2018 shows a drop from the previous two years, which saw a huge amount of trees lost to fire.

However, those involved in the research say this good news is somewhat qualified.

“It’s really tempting to celebrate the second year of decline since peak tree-cover loss in 2016,” said Frances Seymour from the World Resources Institute, who runs Global Forest Watch.

“But if you look back over the last 18 years, it is clear that the overall trend is still upwards. We are nowhere near winning this battle.”

Primary forests are those that exist in their original condition and are virtually untouched by humans.

Sometimes referred to as old growth forests, these areas can harbor trees that are hundreds, even thousands, of years old.

They are critical to sustaining biodiversity and are home to animals including jaguars, tigers, orang-utans, and mountain gorillas.

These old forests really matter as stores of carbon dioxide, which is why the loss of 3.6 million hectares in 2018 is concerning.

“For every hectare of forest loss, we are one step closer to the scary scenarios of runaway climate change,” said Frances Seymour.

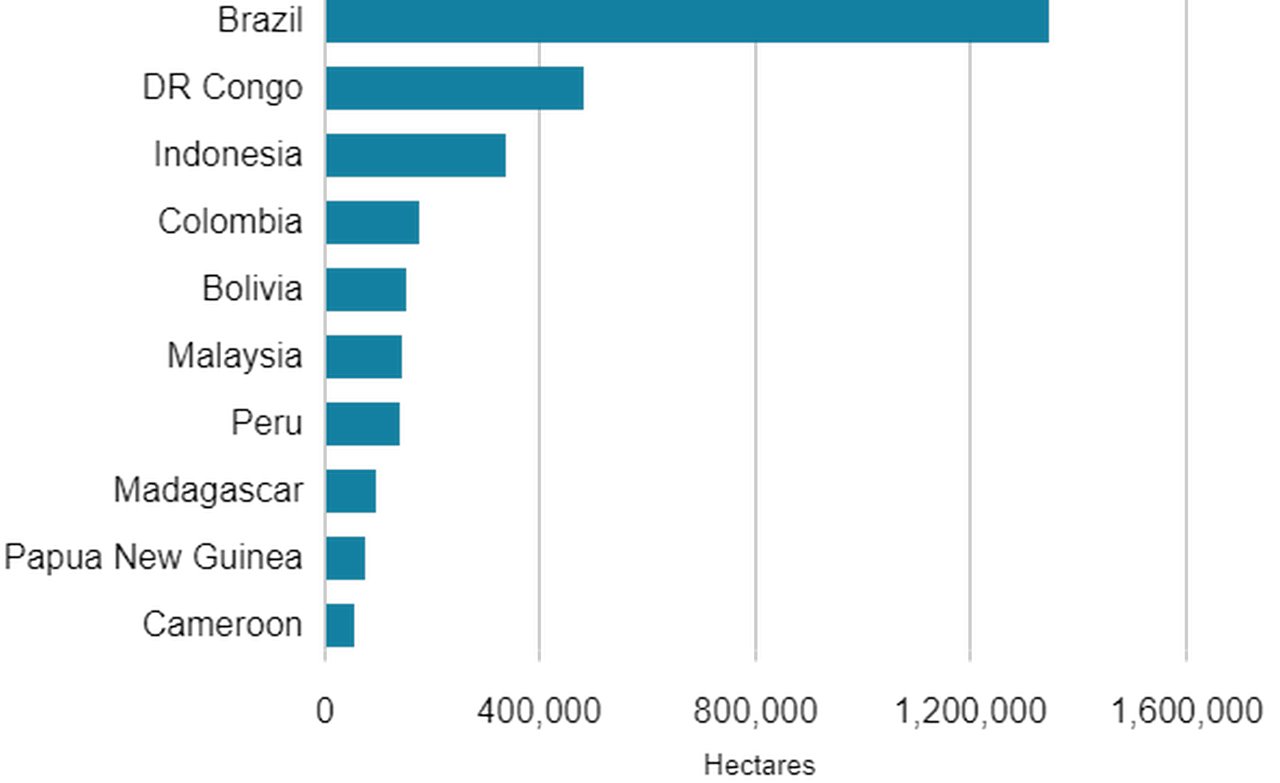

Back in 2002, Brazil and Indonesia made up 71% of tropical primary forest loss. In 2018, these two countries accounted for 46%.

The Democratic Republic of Congo is now the country with the second largest losses by area, while countries like Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru all saw increases in primary forest disappearance.

Colombia continued the dramatic rise first seen in 2016. It’s been linked to the peace process in the country where areas of the Amazon once held by FARC guerrillas have now been opened up to development.

Madagascar lost 2% of its entire primary forest in 2018. That was more than any other tropical country.

Countries including Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire showed the highest rise in percentage terms in losses of primary forest. Ghana saw a whopping 60% increase while Cote d’Ivoire saw a 26% rise.

Most of this increase, particularly in Ghana, is likely to be due to small-scale gold mining. There has also been an expansion of cocoa farming.

Campaigners are concerned that the rise comes despite pledges made in 2017 by leading cocoa and chocolate companies to end deforestation within their supply chains.

Indonesia managed to reduce primary forest losses in 2018 by around 40%, its lowest rate since 2003. The decline is due to a number of factors, including two wet years that limited the fire season.

However, government action has also played a strong role. Protected areas saw big declines in deforestation, while an agreement with Norway to compensate the country for cutting emissions from tree-felling has also made a difference.

The country experienced a major drop in deforestation between 2007 and 2015, by around 70%.

Fires in 2016 and 2017 saw a rise once again. While 2018 was lower, at 1.3 million hectares, it was still above the historical level.

Global Forest Watch notes that in 2018 several hotspots of primary forest loss occurred near or within indigenous territories. The Ituna Itata reserve, home to some of the world’s last uncontacted tribes, saw more than 4,000 hectares of the illegal clearing.

The Global Forest Watch data has been updated by the University of Maryland.

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV