While the world is unlikely to exit the COVID-19 pandemic any time soon, vaccines have given hope and freedom to millions around the world who have lived under tight restrictions for over 18 months.

In the wake of their creation and approval by the relevant medical authorities, the roll-out of coronavirus vaccines has occurred at breakneck speed in some countries.

In the United States, for instance, over 70 percent of American adults have received at least one vaccine dose by the start of August, with more than 50 per cent – some 168 million Americans – fully vaccinated, according to Johns Hopkins University.

The European Union, too, said it was on track to hit its target of inoculating 70 percent of adults in the bloc with at least one dose by the end of the summer.

But when misinformation is so readily accessible and so widely disseminated on social media platforms, it’s becoming an increasing challenge to keep the early momentum of vaccination programmes going.

For instance, Richard Tice, a former Brexit Party MEP and now leader of its successor the Reform UK party shared inaccurate claims on Twitter on August 4 about the effects of the COVID-19 vaccine on children. It was retweeted nearly 800 times.

While the UK’s vaccination programme has been roundly praised for its progress with over 60 percent of adults fully vaccinated, a third of under 30s – some 3 million people – still hadn’t received their first vaccine dose despite being eligible, authorities said at the start of August.

So, why is there reticence towards vaccines now after so many have already been jabbed?

Rising vaccine hesitancy

“For as long as there have been vaccines, there has been what is now termed ‘hesitancy’ or concern or indecision,” Dr Ben Kasstan, a medical anthropologist and a vaccines expert at the University of Bristol, told Euronews Next.

Long before the COVID pandemic, vaccine efficacy and safety were often drawn into public discourse, he added.

“It’s not the first time, but we are living in a very different age as well. We’re living in an age where concerns spread very, very quickly over social media and other social networks in a way that they probably didn’t during the MMR [measles, mumps and rubella] period in the 90s and early 2000s,” Kasstan said.

“We also probably need to understand, and continue to understand, how people make decisions about risk and safety, how they perceive the risk of the coronavirus vaccine versus coronavirus itself”.

Despite the rising prominence of the anti-vax movement, the importance of being vaccinated cannot be overstated, not least due to the looming threat of an increasing number of coronavirus variants. Experts also point out that the risk of being infected by COVID-19 far outweigh the risk posed by vaccines.

“People who have been vaccinated are going to have much less serious and life-threatening symptoms, but they can still experience and be infected with COVID especially with stronger variants,” said Kasstan.

“Whilst they might not be going to the hospital, they might still be getting considerably sick. So, we don’t know what variants are going to develop and emerge in the future”.

What side effects specific to coronavirus vaccines have been reported so far?

“The worst side effect is going to depend on the person and what’s tolerable for them and how they’re prepared and what they’re going to expect,” said Kasstan.

Most common vaccine side effects

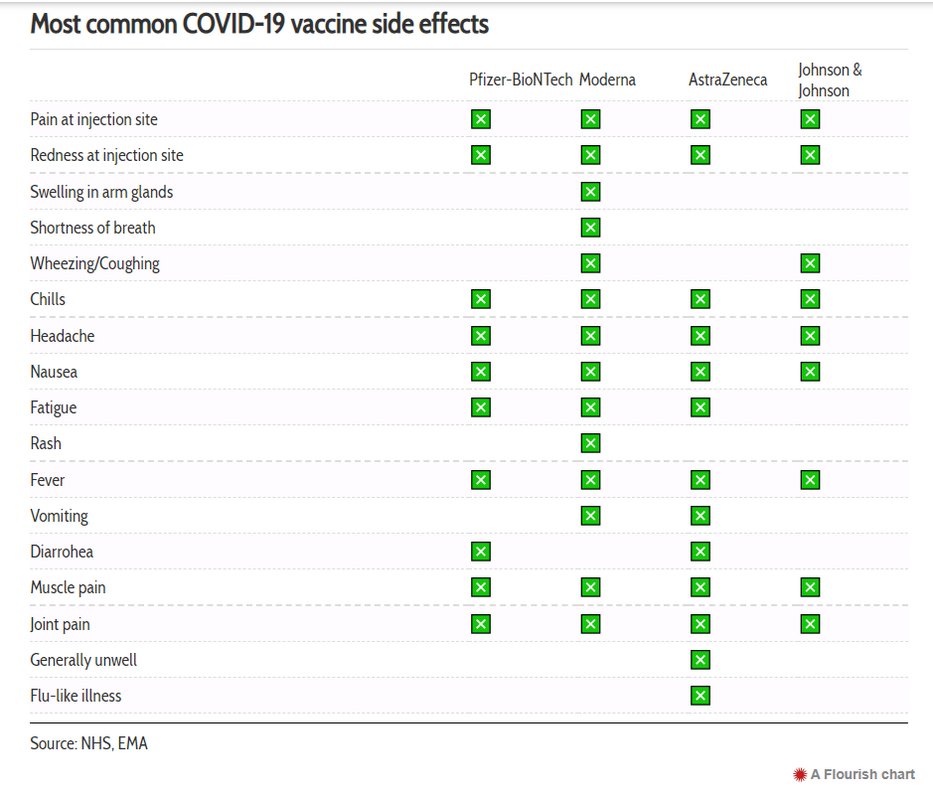

According to the latest data compiled by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), these are the most common side effects experienced by at least one in 10 people after being inoculated with one of the three jabs authorised for use in both the UK and EU.

To date, these are the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna and AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines. In addition, the EU has also authorised the use of the Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) vaccine which we have also included below.

Most of the reported effects have typically lasted a day or two following the vaccine being administered.

How do we know this information is accurate? As is the case with any new medication or vaccine on the market, the reporting of side effects are actively encouraged. The NHS and EMA are continually updating their data to catalogue adverse vaccine reactions which are made publicly available.

The NHS, for instance, relies on the Yellow Card system which allows people to report reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, testing kits and medicines to the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

“[It’s] really important and helpful to understand how COVID-19 interacts with other medicines that might be used for existing conditions and it’s really helpful to gather evidence on side effects,” Kasstan said

“Obviously to help with informed consent and providing information, allowing any kind of confidence issues that people may have. That in itself, that regulatory system around vaccinations and all medical products is really, really important to take confidence from that”.

Rare COVID vaccine side effects

While things like soreness around the injection site and fever are common, there have been rare but nonetheless troubling possible side effects reported.

These are arguably the ones causing the most arresting headlines, particularly around links to blood clots, myocarditis and other serious ailments.

The amplification of these risks without qualifying that the reported instances of these side effects are extremely low is perhaps the real reason behind any concerns the public have had with vaccine safety.

That is not to say that risks should be minimised but the reporting of side effects has meant that protocols and the delivery of some vaccines have been amended and updated.

“There have been some issues around age-related risk to the AstraZeneca vaccine in the UK,” Kasstan said.

“And the delivery strategy and implementation changed accordingly so that younger people under the age of 40 would be offered say the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine instead of AstraZeneca. So at the same time as the programme is implemented, it is responsive to what’s going on, what’s being identified”.

Pfizer-BioNTech

The Pfizer side effect given the most airtime has been the reported risk of inflammation of the heart, known as myocarditis, particularly in young men. While there is so far insufficient data to be able to estimate the rate of incidence, it’s deemed to be an extremely rare side effect.

A preliminary study suggests myocarditis is actually six times more likely to present itself in someone following infection with coronavirus than after a vaccine.

On August 12, the EU said it was investigating the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines after a small number of reports of new side effects, including kidney inflammation, a renal disorder with heavy protein loss in urine and an allergic skin reaction.

Moderna

As well as the ongoing EU investigation into new side effects, which the EMA says is part of a routine update process, the Moderna vaccine has had other less common side effects reported.

For 1 in 1,000 people, there is the potential of developing temporary one-sided facial drooping, known as Bell’s palsy, or swelling of the face (particular for those who have had cosmetic injections). Other side effects include dizziness or decreased sense of touch.

In even rarer cases, myocarditis has also been reported, though adequate data is not yet available to estimate how often cases associated with the vaccine occur.

AstraZeneca/Oxford

Following reports in April which linked the AstraZeneca jab with blood clots, the vaccine was withdrawn or placed under restrictions by several EU countries. These included varying age limits.

Studies have since shown that there is a similar risk of clots as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Rates of deep vein thrombosis – a condition where blood clots occur in the deep veins of the body, typically in the arms, legs or groin – were also similar to the Pfizer vaccine. According to NHS data, only one in 10,000 would be affected.

Johnson & Johnson (Janssen)

In July, the US’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported a number of cases related to a potential side effect of the vaccine, Guillain-Barre syndrome. Around 100 people developed the immune disorder, which weakens muscles and in extreme cases causes paralysis, after receiving one dose of the vaccine.

Officials at the agency described the side effect as a “small possible risk” of getting the vaccine. Most people make a full recovery from the syndrome although one of the 100 cases is reported to have died.

According to NHS data, extreme cases of blood clots with low blood platelets have also been reported which may affect one in 10,000 people.

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV