Microsoft has a lot of sympathy for your point of view. Software updates are inevitable because the world changes, new hardware technologies are developed, new features are needed to cater to new circumstances, and new threats need new defenses. That’s true for every operating system in the fast-moving consumer world.

Previously, Microsoft delivered “big bang” Windows upgrades every three years or so, and these created disruptions of the sort you are facing now. It was even worse for companies with tens of thousands of PCs. It could take them 18 months to plan a migration and another 18 months to roll it out. Programs had to be tested for compatibility, and sometimes, staff needed retraining. People skipped versions to save money and avoid the disruption, though this could make the next upgrade even harder.

The result was that hundreds of millions of Windows users were stuck using less functional, less secure versions of Windows that were up to 10 years out of date. This also held back third-party software, because programmers couldn’t use new features.

With Windows 10, Microsoft solved all of these problems by moving to a system of continuous development. Instead of one huge upgrade every three years, you get smaller updates every six months, spring and autumn, and they are all free. There is less disruption, and eventually, everybody will be using the same up-to-date, most secure and best version of Windows.

Historically, by this stage, I should have written a half a dozen Ask Jack answers about moving to Windows 11. Obviously, Windows 11 was not released in 2018, so we were spared the whole circus that accompanied the launch of Windows 95, XP, Vista and the rest.

Of course, Microsoft’s “new” approach to Windows 10 just made it more like the competition. When you buy an Apple product or an Android smartphone or tablet, you get free upgrades for as long as the device is supported or, in Android’s case, for as long as the device manufacturer can be bothered to deliver them. (Not long, usually.)

Microsoft used to support its software by providing free security updates for ten years, which is far longer than most companies. It also meant the end-of-life (EOL) date was known well in advance, so sensible users could prepare for it.

Windows 7 was launched in 2009, but Microsoft is supporting Windows 7 with Service Pack 1 installed until 14 January 2020. That’s still eight months away, so you have plenty of time to decide what to do.

Windows 8 was launched in 2012, so most PCs running Windows 7 should be seven to 10 years old, and ripe for replacement. However, Windows 8 included a lot of innovations to convert an old desktop operating system into an always-on mobile OS that could run touch-screen apps on smartphones and tablets. Predictably, the touch-screen Live Tiles interface wasn’t welcomed by users who didn’t have touch screens, which was most of us. This kept people – and companies in particular – buying Windows 7 PCs for much longer than usual.

If your PC is one of these relatively recent models, it might be worth keeping, but you should make a realistic assessment of its performance compared with today’s standards.

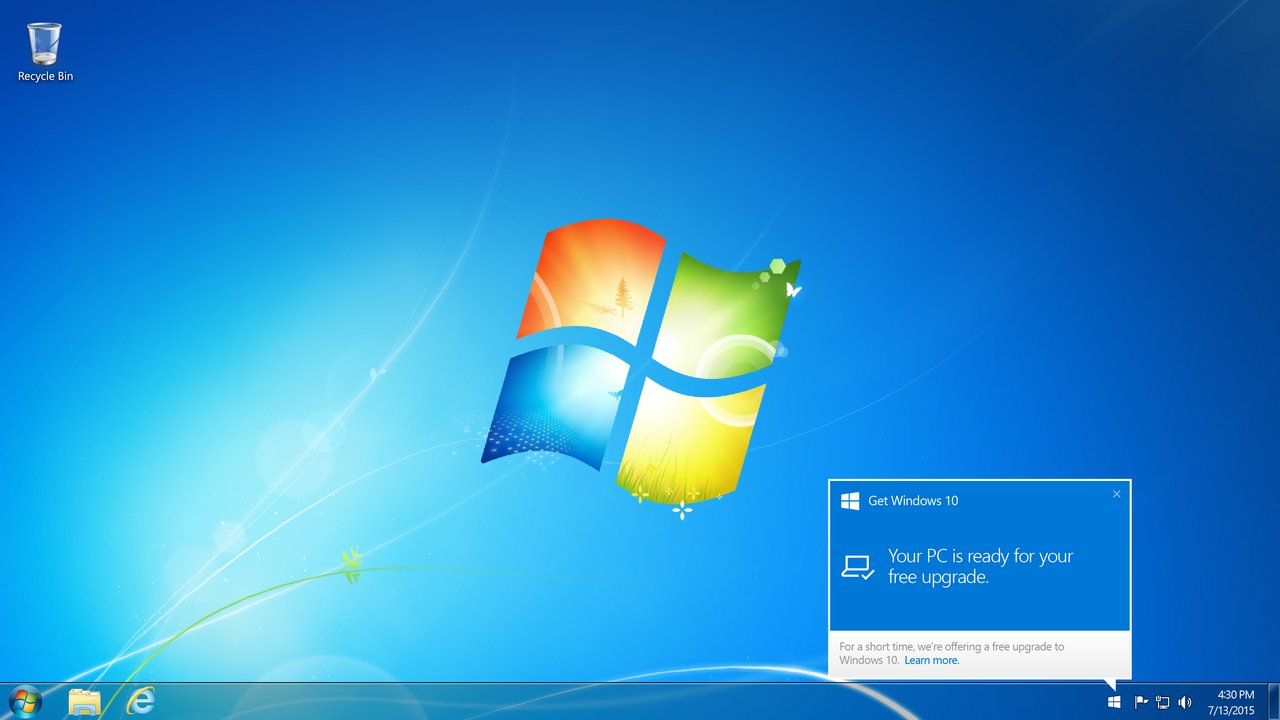

When Microsoft launched Windows 10, it offered to home users running Windows 7 and 8.1 a free in-place upgrade via the GWX (Get Windows 10) app until 29 July 2016. You should have taken it. Once you installed Windows 10, your PC’s right to use it was registered online so you could roll back to Windows 7 and return to Windows 10 later. I did mention this at the time.

However, Microsoft left the door open to free upgrades via its accessibility website until 31 December 2017. According to ZDNet, Microsoft has also continued to provide free upgrades to Windows 10 if you enter a valid Windows 7 product key. To do this, download Windows 10 and use Microsoft’s free media creation tool to create a DVD or USB thumb drive to do the upgrade. Apparently, it doesn’t work every time, but it’s worth a go.

Whether it’s worth paying for Windows 10 depends on how long you expect your PC to last.

Windows is usually great value because the PC manufacturer pays Microsoft a relatively small sum – perhaps about $44 – to install it on a single PC that nowadays should be usable for at least four years. That’s less than $1 a month. If the PC lasts longer, Windows is even cheaper.

But paying Microsoft £119.99 for a copy of Windows 10 is a different proposition. Your old PC would need to last for about two years and four months to bring the cost down to £1 per week.

It might be better to put the £120 towards the cost of a new PC. There are always cheap laptops around in the Windows market. For example, you could get a 14in Acer Aspire 1 with 4GB of memory and 64GB of storage from ebuyer.com for £199.97 or a similar but slower Lenovo IdeaPad S130-14IGM from Currys PC World for £199, or from Lenovo. If you fancy a touch-screen convertible, the Atom-powered Linx 12X64 is reasonably good value at £177.99. You can also buy refurbished systems from suppliers such as Tier1Online and Morgan.

Cheap PCs have relatively slow processors but should be fine for most home uses. Look up the PassMark benchmark scores of their processors and compare them with what you have.

Just avoid cheap machines with 2GB of memory and only 32GB of storage. Windows 10 updates run into problems if you don’t have enough free space.

If you have to keep your current hardware and your product key doesn’t work, you have three free choices. You can stick with Windows 7, use Windows 10 without activating it, or try Linux.

Windows 7 will not stop working when it reaches its end-of-life date. However, Microsoft will stop supplying security updates, which will put your PC at risk. You might survive if you are careful, if you keep all your other software up to date, use a secure browser such as Google Chrome and a strong anti-virus program, run risky programs in a sandbox such as Sandboxie, and have a full backup ready to go if something goes wrong. I don’t recommend this, but some people will try it.

A better option is to install Windows 10 (as described above) and not pay for it. All you have to do is click “I don’t have a product key” and the installation will continue. You will get a watermark on your desktop and you will lose some options to personalize your system, but it will work.

Microsoft wants everyone to use Windows 10 and this could account for its lenient approach to unactivated copies. It may take a tougher line in the future. But if you just need your old PC to run for a while before it breaks down, this should get you through.

The third option is an open source Linux, such as Mint. This is the same price as an unactivated copy of Windows 10, but it has a much steeper learning curve. In other words, you will spend more time learning to use it, and fixing it when it goes wrong. You may also have to find and learn new applications, depending on how much open source software you use on Windows.

Suffering the odd nag that “Windows isn’t activated” is a better deal, if your PC runs Windows 10 well enough. If it doesn’t, Linux is much the best way to keep obsolete hardware in service.

By: Jack Schofield

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV