Scientists have for the first time grown seeds in lunar soil collected by US space agency NASA’s long-ago moonwalkers, an achievement that heralds the promise of using earthly plants to support human outposts on other worlds.

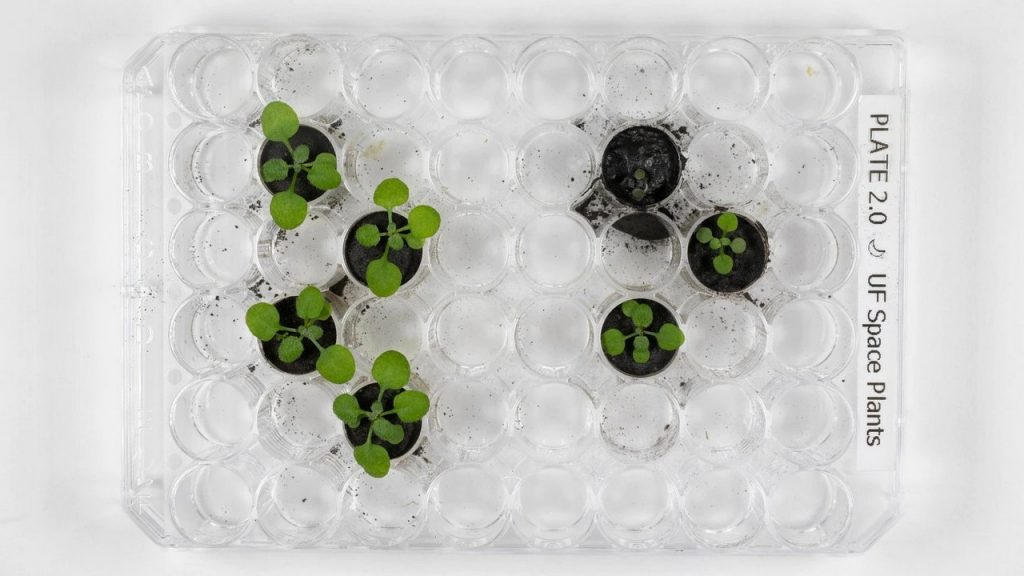

Researchers in the United States said on Thursday that they had planted seeds of a diminutive flowering weed called Arabidopsis thaliana – a type of cress – in 12 small thimble-sized containers, each bearing a small sample of material retrieved during the Apollo missions in 1969 and 1972.

The Moon soil, also known as lunar regolith, has sharp particles and a lack of organic material, differing greatly from the soil on Earth.

It was therefore unknown whether the seeds would germinate. But, after two days, they sprouted and grew.

“When we first saw that abundance of green sprouts cast over all of the samples, it took our breath away,” said horticultural sciences professor Anna-Lisa Paul, director of the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research and co-leader of the study published in the journal Communications Biology.

“Plants can grow in the lunar regolith. That one simple statement is huge and opens the door to future exploration using resources in place on the moon and likely Mars,” she added.

NASA eyes lasting human presence on Moon

NASA is preparing to return to the Moon as part of the Artemis programme, with a long-term goal of establishing a lasting human presence on its surface.

“This research is critical to NASA’s long-term human exploration goals,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “We’ll need to use resources found on the Moon and Mars to develop food sources for future astronauts living and operating in deep space.”

He added the research was also an example of how NASA was working “to unlock agricultural innovations that could help us understand how plants might overcome stressful conditions in food-scarce areas here on Earth”.

At first, there were no outward differences at the early stages of growth between those seeds sown in the regolith – composed mostly of crushed basalt rocks – and others sown for comparative study in volcanic ash from Earth with similar mineral composition and particle size.

But over time differences did emerge with comparison plants. Those planted in the lunar soil were slower to grow and generally smaller, had more stunted roots, and were more apt to exhibit stress-related traits such as smaller leaves and deep reddish-black coloration not typical of healthy growth.

They also showed gene activity indicative of stress, similar to plant reactions to salt, metal, and oxidation.

“Even though plants could grow in the regolith, they had to work hard metabolically to do so,” Paul said.

But researchers stressed the fact that they grew at all was remarkable and said the results provided hope that it may be possible to one day grow plants directly on the Moon, saving future space missions expense and facilitating longer trips.

Fellow study co-leader Rob Ferl, a University of Florida assistant vice president for research, said he felt “joy at watching life do something that had never been done before”.

“Seeing plants grow is an achievement in that it says that we can go to the moon and grow our food, clean our air and recycle our water using plants the way we use them here on Earth. It is also a revelation in that it says that terrestrial life is not limited to Earth,” he added.

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV

Alghadeer TV Alghadeer TV